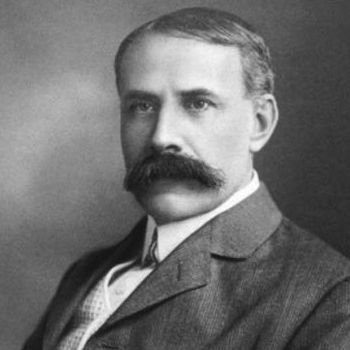

I’ve read a book called “Portrait of Elgar” written by Michael Kennedy recently, and I’ve made a list of things about Elgar that have interested me so far. (Really, there are many but I’ve chosen the most crucially relevant ones just so this blog post won’t get too long.)

So here it is:

6 Things You Need To Know About Elgar

1. Elgar did NOT study composition with any tutor.

Born as a son of a piano tuner & music shop family, Elgar had unlimited access to the scores, particularly Beethoven symphonies.

“In studying scores,” he recalled in 1904, “the first which came into my hands were the Beethoven symphonies… I remember distinctly the day I was able to buy the Pastroal Symphony. I stuffed my pockets with bread and cheese and went into the fields to study it. That was what I did.“

There were a few ‘textbooks’ which he made reference with: Cherubini’s Counterpoint, Stainer’s Composition and Harmony, Sabille Novello’s translation of Succinct Thorough Bass and so forth.

Sometime in 1902, Paderewski was introduced to Cockaigne, one of Elgar’s most successful works, by Ettling. He,at a party, asked Paderewski where Elgar studied. “Nowhere.” Then who taught him? “Le Bon Dieu,” he replied.

2. Elgar was an incredibly wretched man, and possibly could have blossomed much earlier in his career.

Contrary to the popular belief, he was far from your “John Bull” comfortably sitting on a sofa with a cup of tea. Or a gentleman. There’s an unpublished article written by himself of his day trips in his twenties:

“I lived 120 miles from London. I rose at six, walked a mile to the railway station, the train left at seven; arrived at Paddington about 11, underground to Victoria, on to the [Crystal] Palace arriving in time for the last three-quarters of an hour of the rehearsal; if fortune smiled, this piece of rehearsal included the work desired to be heard; but fortune rarely smiled and more often than not the principal item was over. Lunch. Concert at three. At five a rush to Victoria; then to Paddington, on to Worcester arriving at 10-30. A strenuous day indeed; but the new work had been heard and another treasure added to a life’s experience.”

One of the major problems for Elgar seems to have been orchestral rehearsals. At the Covent Garden Promenade Conerts perhaps in 1889, he was compelled to go home despondently with his work unrehearsed because the conductor used up all the rehearsal time for something else. And similar occasions followed a few times.

When he worked on an adaptation of The Wand of Youth for incidental music to be performed at the Kingsway Theatre in 1916, he refused to conduct the performance and did not even go to see it, seeing the state of things which outraged him. He wrote to a friend of the designer: “Your friend has entirely misused any chance this play had of success – he’s an ignorant silly crank with no knowledge of the stage… He ought to be put in a home!” His wife noted “Lovely play & music enchanting – killed by bad setting &c.,” Blackwood wrote to Elgar of the setting in a letter: “suburban, arts and crafts pretentious rubbish.”

3. A lot of people thought he was obscure and strange.

While Elgar was teaching violin at Malvern Girls’ College, Rosa Burley, who was the headmistress there since 1891, once described him as follows:

“His shyness masked the kind of intense pride with which an unhappy man attempts to console himself for feelings of frustration and disappointment … He seemed to me to be a man whose emotional reactions were out of all proportion to the stimulating causes. It was thus very difficult to be at ease with him since he was so manifestly ill at ease with himself. He was one of the most repressed people possible to imagine … enclosed, as it were, by a haunting fear of innumerable disapprovals.”

Elgar confessed to Rosa Burley about his religion. “He told me of post after post which would have been open to him but for the prejudice against his religion, of golden opportunities snatched from his grasp by inferior men of more acceptable views. It was a subject on which he evidently felt bitter…”

4. Elgar also had something of hypochondria.

That’s right. It wasn’t as serious as it may sound, but it tends to happen to someone who’re sensitive, like artists for instance. It’s when one continuously worries that there’s something wrong with their health even though they’re not ill. According to Michael Kennedy, Elgar suddenly ‘took cold’, or his eyes were inflamed, or his teeth ached, or his ears. His letters to friends are full of his ailments – a sudden quinsy or a ‘great & giddy headache’. And this seemed to happen to him when the creative flame was low.

5. He ultimately became the highest-regarded in Britain within the musical realm.