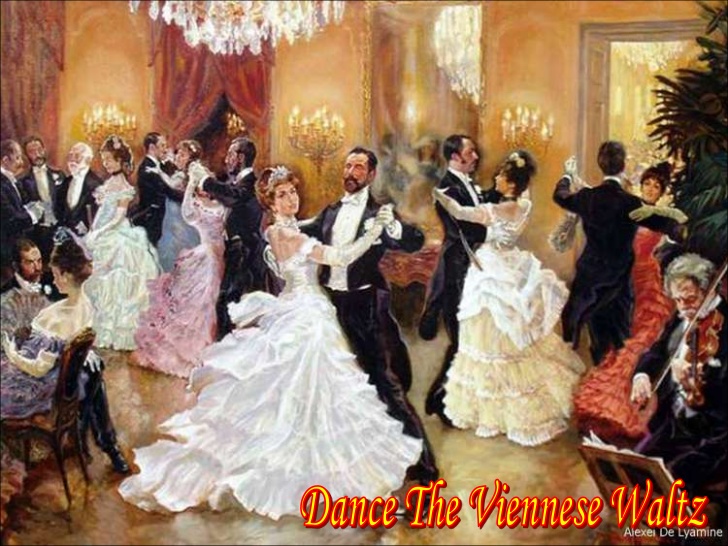

A lot of people will probably and immediately think of Johann Strauss Ⅱwhen they hear the term “Wienner Waltz”(Viennese waltz).

What actually crosses your mind?

For me, not only does the word put me into thinking of Johann Strauss Ⅱ but it also bears a strong association with balls in Vienna where the upper class socialize amongst themselves and dance along with some orchestral music.

And yes, as you may have guessed, Wiener Waltz has its own unique historical/cultural context and its own profound anecdotes.

Before we get into that in a minute, the following concert is approaching its date which is in less than a week:

===================================================================================================

“Wiener Blut” – the concert especially dedicated to presenting some of the most relevant and prominent Viennese repertoire will take place on Sunday 18th June 2017, at Cafe Montage in Kyoto. As spots have been grabbed more and more, you need to book yours before all of them are gone (the maximum is 40). Check the details and reserve your spot here —–> http://www.cafe-montage.com/prg/170618.html

===================================================================================================

That means they could even be all gone in a couple of days, so don’t you dare miss out!

Now, onto the details of Wiener Waltz.

While the city of Vienna enjoyed and benefited from its rich concert life in public halls (one expert noted that,during the 1826-7 season,there were 111 concerts flat), the most popular form of musical appreciation was “ballroom dancing”, particularly in the 19th century ― so much so that people often called it a “Viennese obsession” ―.

In a book “Musical Life in Biedermeier Vienna” by Alice M. Hanson I’ve been viewing, it said that dancing was without doubt Vienna’s favourite pastime and that the sensual waltz mirrored the innermost essence of the Viennese character.

However, there are 3 things you should know regarding the Vienna’s ballroom-dancing condition at the time:

1. Dancing regulations

Did you know that balls were more or less controlled by the Austrian law? Just like other public entertainments, all public balls required to attain permission of the police in advance. This was mostly due to safety reasons, though. In the evenings when balls were being held, the policemen were hired and positioned themselves outside the halls or private homes (yes, you read that correctly) to direct traffic and keep order. Any dancer or musician refusing to leave after the closing hour would be subject to fines or arrest.

Plus, there were restrictions for balls to take place during certain times of the year; namely, any occasions where the calendar marks significant celebratory days – Lent (through the first Sunday after Easter), Advent to Epiphany, Pentecost, Corpus Christi, Marian feasts, birthdays or anniversaries of the royal family, and official days of mourning.

(It has been said that, when Franz Schubert played a bunch of his piano works (some of which were dance music) at a party he was invited to, he received a warning from the commissioner of the police who passed by interrupting the music ― the dance music which wasn’t allowed even in the home since it was during Lent.)

2. Balls as a vital industry for social and pecuniary transactions

It comes as no surprise that balls were expensive to run. This has still entirely been valid in our 21st^century world. According to the resources provided, the total cost of the ball at Apollosaal in 1824, for example, was 408.00 fl.CM (=$200~250). This sum was a lot higher than the salaries paid for most workers, such as factory laborers (they were paid anywhere between 80 and 300 fl. CM per year).

So what actually contributed to the expense the most of all?

Was it the payment for the musicians?

Was it the advertising?

Or was it the foods?

No, no, and no.

Candles.

140 fl. CM just for wax candles.

That comes down to exactly 42% of the whole. You just do the math.

It’s crazy I know, because with that same money they could’ve paid a Kapellmeister’s annual salary!

That said, the profit they made out of holding balls always outweighed the expenditure.

For example, the masked balls which took place on 6th & 8th February 1834 in the Redoutensaal cost them 1,994.46 fl. CM. And YET, since the income was 10,212.48 fl. CM, they managed to raise a total of 8,218.02 fl.CM of profit, which was quite a big deal. More than 5,000 tickets were sold for the ball, and it served several motivations of those who attended ― diplomatic plots, court intrigues, amorous flirtations, and marriage proposals. Joseph Turova noted that balls gained the reputation of being a ‘playground for the city’s adventures and a favourite haunt of married women and widows’.

3. Tax

Another thing which is little-known about the engagement was that, separate from the ticket fees, all musicians at balls whether public or private were charged with a tax of 15kr. on the music. This tax was called “Musik Impost”, which was also imposed upon every restaurant in Vienna offering dance music ― 4fl. 30kr. for public dances and 6fl. for private balls. The months in which the most impost taxes collected throughout the year were generally the winter season from Novemeber through March, which implies how active it was during those times.

According to the author Hanson, many composers benefited from the demand for dance music performed in festive balls ― Schubert, amongst others, wrote waltzes, galops, and quadrilles for special occasions every year from 1822 through 1828. And Johann Strauss certainly upped the state of Viennese dance music to arguably the most sophisticated level.

I’ve been so far talking about all the stories to take you behind the development and prosperity of Wiener Waltz. In the next article, we’ll closely look at how the waltz was being danced in Vienna and its significant cannotations, so stay tuned!